I don’t consider myself a civil libertarian, although that’s a perfectly fine–indeed, admirable–thing to be. On a basic level, I view collective security as the most desirable function of democratic governance; as Isaiah Berlin compellingly acknowledges, the collective security of a democracy’s citizens occurs at the expense of negative liberties. From Corey Robin’s perspective, the state’s growth has occurred in tandem with the mass repression of civil liberties. At the same time, governance tradeoffs exist, which test the strength of a democratic society, but which are also integral to the process of securing a state that protects its citizens. These tradeoffs are frequently false choices, both accidental and intentional: political actors may distort threats for nefarious purposes, but all too often, Berlin’s positive/negative liberty tension represents the unintended consequence of non-resilient policy organizations. Patrick Porter captures this shortcoming in a recent post: the hubristic assumption of preemptive authority mitigates our ability to struggle through crisis, and so policy institutions over-react. Over-reaction bloats policy institutions, which are slow to correct for their growth. As the proverbial crisis dust settles, prevailing institutional interests challenge bureaucratic complacency, leaving scarce space for adequately (small-l) libertarian approaches to policy-making. The ethical purpose of policy-making, therefore, is to optimize collective security and secure individual liberties, all the while acknowledging that it’s entirely impossible to do both.

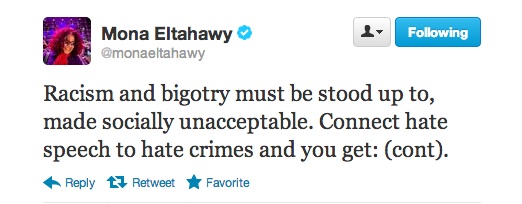

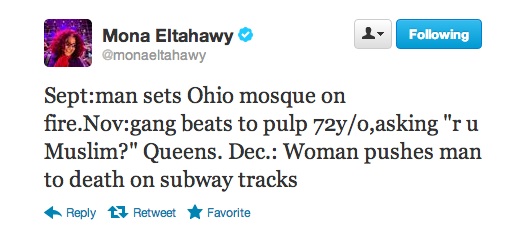

In some circumstances, the real-life dilemmas of collective security may seem realer than in others. The recent murder of Sunando Sen, an Indian-American Hindu, in a New York subway station is an important case in point. During her arrest, Erika Menendez, the woman responsible for Sen’s murder, condemned the victim’s religious background, lining her anti-Hindu rhetoric with anti-Muslim slurs. The Queens district attorney charged Menendez with two crimes: Sen’s murder and a “hate crime,” due to Menendez’s expressed motivation for violence. In the aftermath of the district attorney’s announcement, Twitter was a-twitter with idle speculation: given the subway context, had activist Pamela Geller‘s Islamophobic advertisements played a role in Menendez’s motivations? Egyptian-American journalist Mona Eltahawy, who prompted controversy for her public vandalism of Geller’s subway advertisements, drew an explicit connection between Geller’s “hate speech” and Menendez’s “hate crime”:

While the district attorney’s office will not release the facts of the case while Menendez’s trial is ongoing, coverage of the subway-shoving incident has not indicated Geller’s particular influence in Menendez’s motivations. As Glenn Greenwald observed on Twitter, Pamela Geller represents a singular sub-set of American Islamophobia. While we may discern cultures of violence and Islamophobia that, generally speaking, enable hate-inspired murders, existing evidence does not render Geller’s propaganda more or less influential in Menendez’s motivations. Accordingly, we can differentiate between “hate speech,” which implies a particular act, and “hate culture,” which describes a general environment of social exclusivity and marginalization. Insofar as Menendez’s Islamophobic has occurred in a context, rather than as a consequence of bigotry, the driver (not the cause) of Sen’s murder was “hate culture.”

As I noted on Twitter, this distinction is not semantic, but profoundly relevant to our civic and social approaches to hate-inspired violence. The problem with hate-inspired murder is that one person kills another person, not that they’re also hating the other person’s communal affiliations while doing so. If we view the state outside of its Weberian framework–a monopoly on legitimate violence–and instead as a social institution with unique, if not totalizing access to coercive force, it’s easy to see where a “hate speech/hate crime” approach to inter-communal violence might fall short of the state’s ethical responsibilities to its citizens. Simply put, if the state’s power exists on an even keel with its civil society, its concept of inclusivity should equal all others’. David Cole’s analysis of “hate speech” legislation identifies its libertarian consequences more articulately than I can:

Such laws empower the government, or a jury, to draw lines between legitimate criticism, satire, and public comment on the one hand, and “insulting,” “abusive,” or “hateful” speech on the other. Is there any reason to be confident that government officials or juries will do a good job of this? And as long as the lines are so murky, many people will be compelled to steer clear of legitimate expression that some official or jury might, from its own viewpoint, deem over the line after the fact: this would stifle free speech and lead to self-censorship.

This assessment isn’t new: in fact, it’s standard fare for your ACLU-card-carrying, speech-loving, civil libertarian activist. There’s little dissent on the importance of free speech in a democratic society. More controversial, of course, is the speech’s consequences for mass violence. Susan Benesch, who I’ve mentioned before, differentiates between “hate speech” and “dangerous speech,” a distinction she developed out of an interest in protecting both freedom of expression and collective security. Benesch’s “dangerous speech” is highly context dependent. Compared to Burma, where mass violence against Muslims occurs on a regular basis, American Islamophobia yields infrequent violence because of the strength of U.S. security institutions and the rule of law. As Benesch acknowledges, hate crime legislation, when understood independent of institutional factors, does little to mitigate mass violence against vulnerable minorities, but goes a long way to restricting their libertarian rights.